| HOME | KIDSROCK | TEENSROCK | GEOTOURS |

| History of Rock |

Exploration and Mining |

Directions | Opportunity Rocks! |

GeoTours | Legends of Rock |

Geology FAQs |

More to X-plore! |

Geo-Links | Explore Manitoba |

Turtle Island

There are many versions of the origins of Earth's first peoples. This is the story of the origin of the Ojibway/Anishinabe peoples.

The Great Mystery, or Kitchi-Manitou, put the people on Earth. After many years, the people strayed from their peaceful ways and began to argue and disagree with their friends and families. There was no respect for any living thing, so Kitchi-Manitou decided to cleanse Earth. He did this with water.

The water came and destroyed all the people, except Nanaboozhoo. Some animals that could fly or swim also survived. Nanaboozhoo had a huge log on which he stayed afloat to escape the rising water. He floated on this log searching for land, but none was to be found. He allowed the animals that had survived to take turns resting on the log with him.

Finally, Nanaboozhoo told the animals that he would dive into the water and try to reach the bottom and bring up some earth. He said that with the help of Four Winds and Kitchi-Manitou, he could create new land for them to live on. He dived into the water. He was gone a long time, but when he came up for air, he said that the water was too deep and he could not reach soil.

Then Mahng, the loon, spoke up. He said he would try to dive into the water and

bring back some soil in his beak. The loon was gone a very long time. When he

surfaced, he was very tired. He said that the water was too deep for him to reach

the bottom.

One animal after another tried diving to the bottom, but all failed because the water was too deep. Then a soft-spoken voice was heard. It was that of Wa-zhushk, a little muskrat. He wanted to try to dive into the water. All the animals laughed at him. Nanboozhoo spoke up and told the animals that only Kitchi-Manitou could judge the little muskrat. If he wanted to try, he could.

Wa-zhushk dove into the water. He was in there for a very long time. Nanaboozhoo and all the other animals were worried Muskrat had drowned. After a long time, they saw something floating to the surface. They pulled Muskrat onto the log – he had drowned. All the animals and Nanaboozhoo began to mourn. Then one of the animals noticed that Muskrat had something in his paw. It was a ball of soil. Wa-zhushk, the muskrat, had sacrificed his life so that a new life on Earth could begin. As Nanaboozhoo took the soil from Muskrat's paw, Turtle swam forward and offered his back on which to place the soil. Everyone believed that with the help of Kitchi-Manitou, they could make a new Earth. As soon as the soil was placed on Turtle's back, the wind began to blow from all four directions. The tiny piece of soil began to grow. It grew and grew until it formed a mi-ni-si, an island in the water. The island continued to grow, and Turtle was able to hold it on its back. Soon there was a huge island in the middle of the water. Everyone sang and danced in happiness. |

|

According to legend, Turtle Island formed the continent of North America.

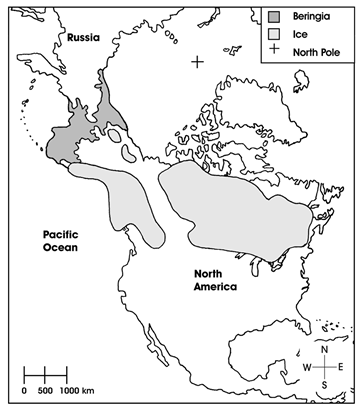

Beringia

Archaeologists have developed numerous explanations about how First Nation peoples arrived in North America. One of the most widely accepted theories is that an ancient land bridge once spanned from Asia to North America. It is believed that North America’s ‘first people’ arrived some 30,000 to 35,000 years ago during an ‘Ice Age’ period. At that time, as ocean levels dropped and turned to ice, a frigid ‘Beringia’ land bridge may have formed, allowing hunters to cross from one continent to another. This may explain why certain ‘Ice Age’ artifacts which have been discovered in North America are similar to artifacts found in Asia from around the same historic geological era. The artifacts may well have been left behind by ‘Ice Age’ hunters as they pursued herds of buffalo, mammoths, bison, and caribou into North America. Image is reproduced with the permission of Portage & Main Press, from Hands-On Social Studies, Grade 6 (2005) |

|

Manito-wah-paow

The name ‘Manitoba’ was given to the province in 1870 at the suggestion of Indigenous Métis leader, Louis Riel. The word was derived from a Cree word ‘Manito-wah-paow’, meaning “...the narrows of the Great Spirit..." which describes the narrowing of Lake Manitoba near its center. As pounding waves echoed across the lake, the Indigenous people believed it was the stirring drumbeat of the Great Spirit, the mighty ‘Manitou’.

Indigenous people who settled in Manitoba were highly skilled in traditional land use methods, including hunting, fishing, and the quarrying of minerals. Minerals were mined and carved for tools and other uses. The mineral ‘hematite’ (red ochre) was ground into a fine powder, mixed with water, and used as decorative body paint during sacred rituals, and for the colourful telling of ancient Aboriginal legends painted on rocky cliffs. Rocks and minerals were regarded by Indigenous people as ‘gifts’ from the Creator. Large rocks and stones were sometimes selected and placed in sacred healing and teaching areas. The stones were placed on the ground to correspond with the sacred Four Directions. These unique rock formations, many of which took the shapes of animals, people or a ‘medicine wheel’, can still be found in Manitoba, and are known as ‘petroforms’. The petroforms of Manitoba represent a historical record of the Indigenous people’s long history and close connection to the land.

Traditional Knowledge

The traditional knowledge (cultural and worldview) of the Indigenous people provides valuable insights into the importance of their way of life and unique cultural landscapes.

Aboriginal knowledge, which was developed through many years of traditional practise and wisdom, was handed down by elders within close-knit communities from generation to generation. Sharing of traditional knowledge was carried out with great care and included the study of weather patterns, waterways, animals, plants and seasons. The cultural insights delivered by elders over many generations continue to be a foundation for Aboriginal communities even as they grow, engage, and explore new opportunities within the modern-day mining and minerals sector. Today, many Aboriginal communities seek to share the ancient knowledge of their forefathers by incorporating traditional land use methods and resource planning alongside modern industry, economic, and community development initiatives.

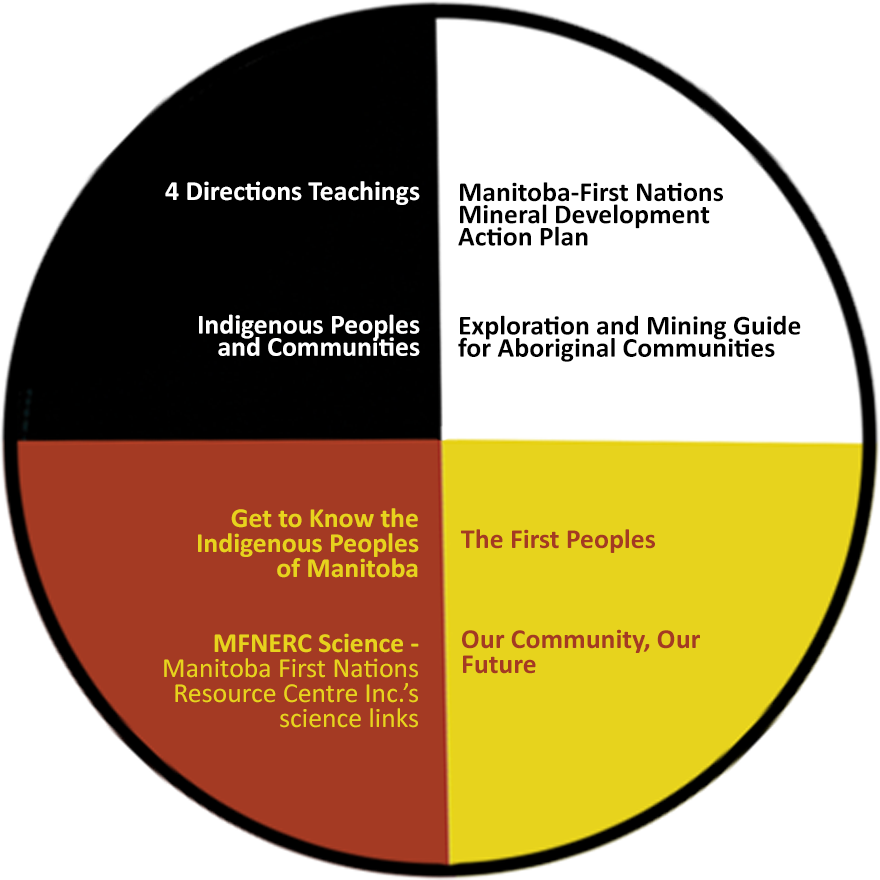

Learning Circle

Explore the Learning Circle links to learn more about the Indigenous culture, Indigenous Mining Communities in Canada, the Aboriginal Canada Portal, and more.